Okumidori おくみどり

Okumidori was registered in 1974 at the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry registry as Okumidori and registered as cultivar N°32 (茶農林32号). Developed at the Kanaya National Institute of Vegetable and Tea Science.

Status: 🌱

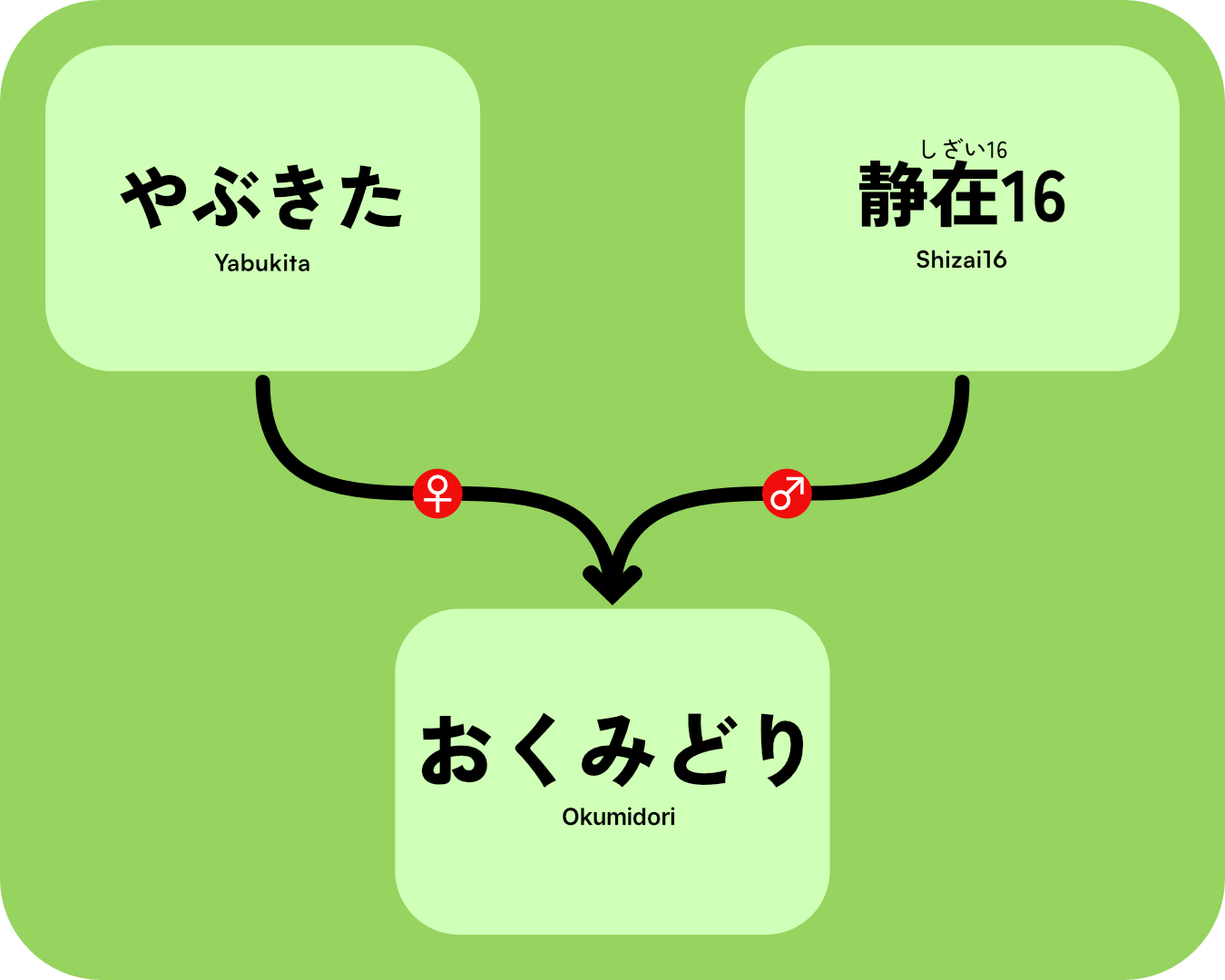

Genealogy

♀: Yabukita やぶきた

♂: Shizai16 静在16

History

Okumidori was registered in 1974 at the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry registry as Okumidori and registered as cultivar N°32 (茶農林32号). Developed at the Kanaya National Institute of Vegetable and Tea Science.

Registered as a crossing of Yabukita as the flower parent and Shizuoka Zairai No.16, also known as Shizai 16 or S16, as the pollen component (more about this in the second part of this article later on). The original release paper explains its promotion as a cultivar that allowed it to expand the harvest period. It is a late budding cultivar harvestable around eight days after Yabukita, allowing factories to have a better distribution of harvesting periods and spread the window of harvesting and processing with a high-yield cultivar. Although it's a cultivar registered for Sencha, it's also used for Tencha production and Gyokuro.

Although registered in 1974, it didn't immediately become widely used even though it was understood to be an excellent cultivar for some years. One of the main reasons for this is that the price of its first harvest was low because it is a late-harvesting cultivar. In recent years, even early-growing teas are cheap if they are not of good quality and even late-growing teas of good quality trade at relatively high prices. From around 1990, Okumidori attracted attention as a high-quality, high-yielding cultivar, and the cultivated area increased. The demand for ready-to-drink (RTD) bottled tea has shifted the market. Beverage manufacturers are looking for teas with a relatively cheaper price and a mild taste. For this reason, some tea producers are beginning to introduce late-growing cultivars, such as Okumidori, to increase the utilisation rate of tea factories and proactively reduce production costs. Okumidori's quality characteristics, typical of green tea, are highly regarded, and its yield is high even in second and third harvests.

Breeding crops such as tea has several other challenges that also affected its popularisation aside from the economic factors. Since it is a perennial woody crop, the time for flowering and crossbreeding slows down the generation turnover, making breeding less efficient. Furthermore, the self-incompatibility of the tea plant made it difficult to analyse the transmission of traits, so the efficiency of the selection was low. Methods such as Quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis and DNA marker techniques linked to specific strain traits have also developed, increasing the efficiency of the breeding process.

On the other hand, in the 1990s, Yabukita peaked in popularity, and the availability of land and willingness to replant with a new cultivar was low. For this reason, even if excellent new cultivars existed, they were not easily spread. According to a paper released in 2006, Early and late-growing cultivars have seen an increase in cultivation area due to the concentration of the harvesting season into a tiny period. Due to the overuse of the Yabukita cultivar, it overworks the harvesting period and the processing factories. By growing cultivars other than Yabukita, the harvesting window is longer, which also lengthens the hiring time of seasonal workers, making it a more attractive job for them, but also lowering the pressure on the processing factories, which could also mean more spread out production costs. In turn, this means there is a need for more control in the fields, as each cultivar might have different needs or pests to control. The producer and consumer education, awareness and preferences are also increasing. The approach to the market is also changing. Although small, specialised products like single cultivar teas and more product information regarding the processing or blends at buying time are increasing, as well as the number of producers experimenting with black tea production or half-withered teas.

Another important factor driving this spread is that the popularity peak of Yabukita was around 35 years ago. A big part of tea farmers have or will soon begin to replant some fields, with the unique consequences it has to tea in the propagation of new or existing cultivars. Once replanted, it is not possible to harvest tea leaves at a profit for 4 to 5 years due to, among other, the size of the bushes, which need to grow from seedlings into full-grown bushes. In addition, when working with new cultivars, there is a period to find the correct processing methods and settings for that specific cultivar. Due to the popularity of Yabukita and the bottleneck in production it created, it is difficult for some farmers to deal with small-lot single-cultivar teas due to the enlargement and automation of their tea factories. The historical background of Yabukita is a heavy factor in the spread of new cultivars.

Although this movement has only just begun, changes in consumption, the spread of RTD plastic bottled tea, and a rise in consumer demands for the safety and security of their products are diversifying the breeding and selection goals. And we will probably see some differences in the cultivars to come. Like the newly released Shizuyutaka and Yumesumika, a perfect showcase of the breeding focus nowadays, Shizuyutaka focuses on high yield, doubling Yabukita. Yumesumika's main characteristic is a 1.5 times more aromatic sweet and flower aromas than the already aromatic Koushun. Focus has shifted nowadays on high-yield growth, selection of cultivars with distinctive flavours or aromatic characteristics, pest-resistance cultivars, low fertilization adapted cultivars and cultivars with functional components like the high levels of anthocyanin of Sun Rouge or methylated catechin levels of Benifuki.

The market seems to be moving towards where cultivar diversity is needed to diversify production, increase yields and cater to newer market segments, especially abroad. This situation is also transforming the breeding goals for tea cultivars, together with the implementation of technologies like the QTL and DNA markers mentioned above, as well as changing the overall breeding and propagation programs. Other developments include efforts to promote cultivars inside the prefectures by offering assistance in their propagation and cultivation, but also evaluation after processing to review the teas made with those new cultivars and accelerate its promotion and market availability after breeding and registration. A success story for Saemidori spearheading this type of initiative in Kagoshima.

Cross-breeding green tea cultivars introduced after the war began to rise in the 1970s, but in 1974, when Okumidori was finally registered, Yabukita rapidly proliferated, quickly reducing the amount of Zairai (seed-grown) tea fields. Generally speaking, with woody crops, the supply of seedlings of new cultivars is small at the beginning of cultivation due to being reproduced by cuttings, and the availability of grown trees is low, making it difficult for a rapid spread. In the 1970s, there was rapid replanting of seedlings from native Zairai to Yabukita, and there were not many other cultivars available or large quantities of seedlings to interrupt this tendency.

The interest and promotion of the cultivar began sometime between 1990 and the early 2000s. According to a 2006 paper, the amount of land using Okumidori was about 715ha in 2002, with a projection of over 900ha in 2005 with non-harvested and new fields included. Making Okumidori the 4th cultivar in terms of growing area, but still at around 3% of used cultivars. It is one of the most commonly grown cultivars, with Yabukita, Yutakamidori, Saemidori, Sayamakaori and Samidori. Data from 2022 shows Okumidori being the 3rd most grown cultivar in Shizuoka and Aichi and 2nd in Kyoto. That is not considering the group of "other cultivars" where most other cultivars get grouped into this statistic. Ten prefectures adopted it as a recommended cultivar in this 2006 study, mainly the Tokai, Kinki and Kyushu regions. Nowadays, it's grown in 21 prefectures.

Okumidori was cross-bred in October 1953, with seeds collected in October 1954 and planted in the nursery in April 1955, where successfully germinated seeds were grown until April 1959, when the individual selection of the different seedlings began. An initial selection in 1960, where Okumidori was pre-selected, gave it its ID number 6112. In 1961, it was selected again in a second round that focused on the selection of cuttings, and then in 1962, another round of selection focused on nursery characteristics. The selected bushes were planted in a field in March 1963 to perform strain comparison studies from 1963 to 1973 and their characteristics from 1967. Okumidori underwent these tests under the strain name F1NN29.

While being developed in the Kanaya National Institute of Vegetable and Tea Science, parallel studies were carried out in other prefectures from 1969, with more joining every year until 1972. In 1973, with strain and test site data performance considered excellent, it was submitted as a high-yield late-growing sencha cultivar candidate at the general tea industry meeting in February 1974. In June of the same year, it was registered in the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry registry as Okumidori and registered as cultivar N°32 (茶農林32号). Other candidate names submitted were Okufuji, Kunimidori, Makimidori, Okujishi and Bansui.

Characteristics

Okumidori is a high-yielding cultivar, budding around 8 to 11 days later than Yabukita and can be harvested 6 to 8 days after Yabukita. It has vigorous growth, with one more main branch than Yabukita (6 against 5), and a spreading growth habit. Tea with Okumidori leaves material has a refreshing, clean aroma and taste. Okumidori is a cultivar to replace or grow alongside Yabukita due to its higher, good colour and relatively little loss of quality even if the harvesting season is delayed. The yield of fresh leaves is high for all three harvests, with an average of the three harvests that doubles that of Yabukita yields in most of the test areas.

The tree is quite strong with an upright shape although slightly shorter with good rooting of cuttings as well. With higher survival rates than Yabukita, 90% against 84% and adult seedling survival rate is 85% against 80%.

It can be grown in warm and cold regions but needs care against frost damage in areas with large temperature differences. It has strong cold tolerance and is less prone to defoliation. Although it grows until late autumn, it is susceptible to damage from laceration-type frost damage in warm regions if fall fertilizer application is late in the year, as the new shoot will grow in late autumn. In terms of disease resistance, it is weak against anthracnose, but resistant to ring spot disease caused by Pestalotiopsis longiseta. Deep pruning and trimming regrowth after the second harvest are better than after the first tone to prevent overgrowth in autumn and recover faster for next year's spring harvest. There are no other special considerations for cultivation. Fertilizer management and application is similar to Yabukita.

As sencha, the new buds grow well, and the length of the internodes of the buds tends to be longer. So stems may stand out during processing, but the fresh leaves are bright green, so the final product has a bright green colour. It has a high bud number during the picking season and a slightly higher bud weight than Yabukita. A chemical analysis reported similar tannins and water-soluble compound levels as Yabukita in 1973.

The tea has a fresh aroma and a good taste while being neutral and blending well with other cultivars, so it is not only used as a single-origin tea but also as a blend component because it does not cover the characteristics of others. Okumidori does not particularly stand out, getting similar results as Yabukita in tasting evaluations of Sencha. On the other hand, it is an excellent cultivar commonly used for Gyokuro and Tencha production. One of its most interesting characteristics is its body texture as Matcha. Unfortunately, I could not find data on this subjective experience I have shared with several people after trying different Okumidori matcha from several farms.

It can be grown anywhere in the country, and seedlings are available through multiple nurseries nationwide.

References

Katsuo, Kiyoshi, et al. ‘A Newly Registered Tea Variety “Okumidori” Suitable for Green Tea’. Chagyo Kenkyu Hokoku (Tea Research Journal), vol. 1975, no. 43, Aug. 1975, pp. 1–12. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.5979/cha.1975.43_1.

The tea breeding group ‘Saemidori’ and ‘Okumidori’ (Representation; Yoshiyuki Takeda). ‘Breeding of the Early Budding Cultivar “Saemidori” and the Late Budding Cultivar “Okumidori”’. Breeding Research, vol. 8, no. 3, 2006, pp. 113–17. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1270/jsbbr.8.113.